Blog

Internal Dialogue of a Bereaved Mother

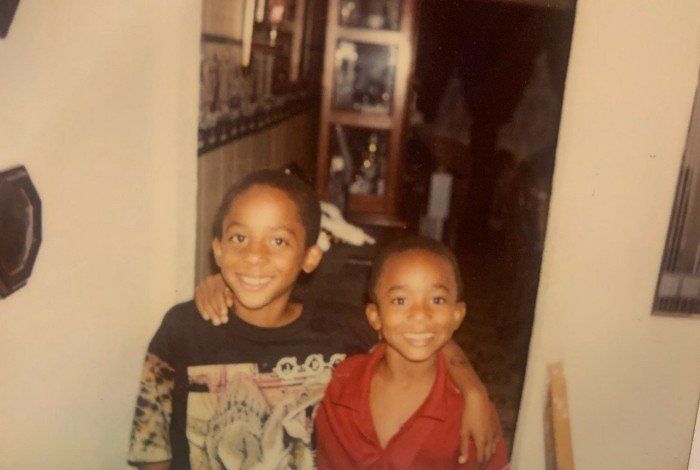

There’s no greater blessing that God has bestowed upon me, than motherhood. Not only has it allowed me to love unconditionally, but experience the gift of unquestionable love that only a child can give. Raising my two boys alone as a single mother would also prove to be one of the biggest challenges I faced as a woman; the overcompensation to alleviate missing father blues, raising black boys in a society that’s unaccepting of them, and unforgiving of their mistakes, producing latchkey kids, and working extremely hard to dispel the popular folklore that makes single motherhood worse than a tale told over a blazing campfire.

When my sons were little, I never thought much of the world around us. As they got older, and times started to change, I became more concerned with peer pressure, and unfavorable decision making. The staggering difference in the treatment of African Americans within the

Criminal Justice System had also gained spotlight, which compounded my fears. When my youngest son, Carrington, was sentenced to serve time in the Georgia Department of Corrections; the judge, the prosecutor, even our own attorney made us feel ostracized. I walked out of that courtroom broken; feeling I had hit my lowest point. My seventeen year-old baby would be housed with grown men – some old enough to be his father, even his grandfather - who had committed some of the most heinous crimes you could think of. How would we ever get through this, I thought.

• • •

But time went on, and “that day” became two years ago, then four, then six years. Although, the days and nights didn’t come and go without tears, fears, sleeplessness, and many prayers; Carrington and I were getting through this difficult period in our lives the best we knew how. After almost seven years in the Georgia Department of Corrections, “home sweet home” was finally in the forecast. We had planned out everything for this most anticipated occasion; the moment we talked about and prepared for no more than a day after his sentencing would soon be arriving. Then one night like a plot twist in a movie, I received a call from another prisoner that shook my core; Carrington had been stabbed to death. I went from planning my son’s welcome-home party to making arrangements for his memorial service.

Just like that, I had been kicked out of the club of the “mothers of incarcerated kids,” and forced into this “bereaved parents’ club.” Before March 20th, 2020 I had only a shallow idea as to what it felt like to lose a child; boy, was my inkling off. It is something ungodly. It is a phenomenon that only the members of this club can discern. I only thought I was at my lowest the day Carrington was sentenced to prison; I now felt like I was drowning in an ocean of darkness. Nothing I knew about life, death, or God had prepared me for a pain so colossal. It would have felt more natural to had gone blind. I didn’t know if I’d make it through the night. And I simply didn’t care. If a person can really feel dead - I felt it that cold night in March. What was almost as bad as the initial injury of losing Carrington, was waking up the next morning with the realization that he was truly gone; that I had not dreamed this horrible ordeal, but the loving being I had birthed, nurtured and loved was gone forever.

You see, life ceases, but love is immortal; it transcends even the grave. If you’ve ever pondered over this adage; just ask a mother who’s buried a child. There’s something about the journey of a bereaved mom. She attempts to carry on with life, although there’s very little life left in her. By the Grace of God, she chooses to get up out of bed each day, not only because those who are living count on her to do so, but so does the spirit of the child she lost; to be his voice; his truths teller; his legacy keeper. And as a mother who raised a child who had a zeal for life, I know above anything else he would root for me to be okay. He will always be my unseen cheerleader.

Each morning as the sun competes with the moon for the day, and God blares the alarm of my internal clock, I’m forced out of bed by the consciousness of Carrington’s voice, “Get up, My Dear. We are not done yet.”